How to develop explosive goalkeepers

While the global game of football is generally considered an endurance sport (although sport science would classify it as repeated-sprint/sprint-endurance), goalkeepers are the speed and power athletes of the game.

The tragedy is, in my dramatic but professional opinion, that keepers are trained almost identically to field players - with the exception that they also have to complete goalkeeper-specific training sessions.

What’s so bad about that? The more, the better, amirite?

The problem with holding keepers to both the field player and the keeper training standard is twofold:

A large portion of field player training is irrelevant to (and potentially counters and works against) accurate, efficient goalkeeper training.

The possibility of overloading (or overtraining) a keeper who is held to both standards of training is high - even though they “don’t move that much”. Load management is required here.

In my experience, goalkeepers are the afterthought in training sessions. They serve as netguards for the field players, warm up and run and cool down with field player-specific workouts, and little else. Due to time and personnel constraints, goalkeeper training is usually additional to that team training.

And, thus my question: is this really helpful?

Training a keeper like a field player and then like a keeper… for what? Does this make them more explosive, more agile, healthier, or more consistent? Or does it elevate their chances of becoming slow, out-of-shape, and less powerful?

Let’s take a closer look at what specific strength and conditioning training for goalkeepers - not field players! - should look like by analyzing the positional demands and what fitness qualities are required to meet them.

STRENGTH TRAINING

Maximal strength is, for goalkeepers, necessary as a foundation for speed and power, as well as to lower their injury risks.

What does that mean in practical terms?

Keepers need to lift progressively heavier weight, at least 1-2x per week in-season and 2-3x per week in off- and pre-season, in order to improve their capacity for strength (literally “getting stronger”). This sets a foundation for their jumping, flying, and diving in all directions, yes, but being strong can lower a keeper’s risk of shoulder, back, knee, and foot (re-)injury.

NO, YOU WON’T LOOK LIKE A BODYBUILDER.

An important distinction when discussing lifting programs is between “maximal strength training for sport” and “bodybuilding”.

Yes, adding pure mass will make a goalkeeper stiff, less mobile, heavier (making it harder to move quickly in all directions), and potentially more tired. This would skyrocket their risk for injury, likely make the athlete slow, and completely defeat the purpose of strength training to improve athletic performance.

Luckily, it takes years of 4-6 sessions a week in the gym of progressive hypertrophy training, nutrition tracked down to the calorie, prioritized recovery, and a consistent caloric surplus (always eating more calories than you burn in a day) over months and years to achieve a bodybuilder’s physique.

A soccer player of any kind could never achieve this by accident, as they simply run too much, recover too little, eat too few calories to keep building huge amounts of mass, and spend too little time in the gym. Please do not worry about “becoming a bodybuilder” by adding in heavy strength training.

YOU’LL LOOK LIKE A GOALKEEPER.

Back to our 1-3 sessions a week.

In the off-season, hypertrophy training (2-4 sets of 6-12 repetitions at moderate weight) can be helpful to improve baseline strength and add a tiny bit of muscle to an athlete who has never trained before. This is Step One, and is something I revisit with most of my keepers in the off-season cycle.

In the weeks leading up to pre-season, focus starts to shift from hypertrophy (strength-endurance work) to strictly maximal strength. This sort of training is defined by it’s 3-5 sets of 1-6 repetitions at high load and intensity, taking athletes over their 85% effort. We use those last weeks of off-season to concentrate completely on gaining pure strength, then test 3RM in the squat, deadlift, and either bench or overhead press (depending on the athlete), so that we have a baseline number to work with throughout the pre- and in-season.

In the pre-season, power and speed become of prime importance, and maximal strength is a compliment to this. It is still possible to get stronger during this phase, and strength becomes transferrable to the position… meaning that athletes begin to see their work in the squat and deadlift transform into better vertical or broad jumps, their lateral lunge strength into lateral bounds and dives, and their upper body strength in the ability to hold and send balls (medicine balls or soccer balls). Strength exercises should become more specific to what the athlete is doing on the pitch, but should stay in that 85%+ effort range with up to 6 repetitions per set.

During the season itself, performance is the priority. Although players can get stronger during this part of the cycle, maintaining maximal strength becomes a minimum requirement for injury prevention and not necessarily an indicator of how well a player is performing. Load management is critical in the season, meaning that strength work likely drops from a total of 10-25 sets of work to maybe 8-12 sets at that 85%+ sweetspot. Although maximal strength training should never be completely taken out of the plan, even during the in-season, it should be adjusted and fit in to the schedule in a way that is less taxing, helpful for recovery, and maintains the athlete’s strength qualities to limit injury risk.

Maximal Strength Exercises:

Heavy deadlifts and their variations (RDLs, snatch-grip, HexBar, single-leg, etc.)

Hip Thrust (1- or 2-legged, with barbell or plate on the hips)

Squat Variations (front, back, Zercher, box squats, etc.)

Bench Press + Incline Shoulder Press (with dumbbells and/or barbells, 1- and 2-armed)

These exercises make up the meat of the session, with the most time, effort, and rest dedicated to this section of the workout. Your repetition scheme should stay within 3-5 sets of 1-6 repetitions per exercises, with high intensity (meaning weight is at 85% effort/percentage of 1RM or more) through each rep. For maximal strength 2-3 minutes of rest between sets is required to achieve enough recovery and get the most out of each set.

Accessory Strength Exercises:

Heavy Rows (1-arm DB rows, Pendlay rows, Seal Rows, seated cable rows)

Pulldown variations (chin-ups, neutral-grip, rope pulldowns, wide-grip, etc.)

Pull-up variations (chin-ups, neutral-grip, wide-grip, narrow-grip)

Split Squats (front foot elevated, goblet-hold, bulgarian/rear foot elevated)

Heavy Carries (suitcase carries, 2-arm carries, KB carries, front-rack carries, Zercher carries…)

It is hard for me to call these “accessory” exercises, because that makes them sounds so much less important than they really are. Keepers desperately need upper-body pulling strength, shoulder stability, grip strength, and single-leg strength and control. These exercises compliment the maximal lifts listed above, but the rep scheme and load requires different numbers. For accessories, which always come after the maximal strength lifts, choose a cadence of 2-3 sets of 4-8 repetitions, adjusting the weight and fatigue level as needed. These movements should still be challenging, but not absolutely exhausting.

Rest should be 1-2 minutes between sets; remember that we are not training like bodybuilders who need hundreds of reps per bodypart per day, but this is also not a conditioning session, so the athletes need appropriate rest to get the most from their workouts.

POWER TRAINING

What anyone who has ever watched any football match or a nice goal highlight reel on YouTube can tell you about goalkeepers is that they fly - they jump in all directions, dive, lunge, sprint, and contort in the air, doing anything they have to in order to hopefully put a hand on the ball. It is incredible.

While building that capacity for strength is critical for keeper health and also for maximizing power and speed, heavy lifting is sloooooow and goalkeeping is explosive.

What’s the catch? How can we combine those seemingly opposite elements in training?

My guidelines for power training:

Start at the beginning. For athletes brand new or returning to power training or fitness training in general, kettlebell swings, medicine ball slams, and low-intensity plyometrics (like pogo jumps and low hurdles) are the primary tools of the trade. These methods allow keepers to get comfortable absorbing and generating progressive levels of power repeatedly (called “ballistic training”), laying a basis for a quick reaction time and 100% effort in each repetition. As players adjust to this training, add load (weight) and intensity (speed, effort, etc.).

Explode laterally! Keepers do this anyway. If you’re going to dive, jump, or lunge sideways in a match, train that as well. I recommend medicine ball slams: rotating/side slams on the ground, side tosses to a partner or against a wall, and half-kneeling versions. Don’t just toss the ball casually; actually throw it. If you can demolish a medball in training, handling a soccer ball will feel like child’s play in comparison.

Train on one leg! As is also the case with field players, sprinting is done on one leg. Jumping and lunging, however, also tend to be one-leg dominant, so learning to absorb (land) and generate (jump) power on just one leg is critical for explosivity, yes, but also for lowering risk for injury.

Get great at decelerating/landing AND accelerating + jumping! Similar to the last point, but this is important for athletes for have never experienced speed, power, or progressive and coordinated strength training. While most of us think we know how to land and how to slow down, the reality is that many players develop compensations for movements that they can’t quite master otherwise, and this can lead to injury and a lack of efficiency. Revisiting how to land, how to slow down, and how to change direction (all “absorption”) before concentrating on the take-off part (the “generation”) can be very helpful, even if it feels silly. Always check your brakes before you slam on the gas.

Sprint over 10m @ 100%! This is critical for keepers, before 5-10m sprints under pressure is their wheelhouse, and that should be the focus of their speed training. My favorite protocol for this, which is especially helpful for athletes new to power or speed training, is the 10x10 Protocol, meaning the player runs 10x 10m sprints at 100% effort (the start is irrelevant, but a falling or plyometric start can be useful here), with 45-60sec rest between reps. Why so much rest? Because athletes need rest to recover and maintain their explosivity. This also mirrors game scenarios, with lulls between keeper actions in a match. See the “Conditioning” section for more on this.

Add in a barbell and technical lifts (if you have the time and experience to learn it). Especially in team settings and during the in-season, I am not a fan of Olympic Lifting. Although the clean, jerk, snatch, and their components can be useful in developing power efficiently, I prefer to keep this to the off-season, when time can be used for teaching the technicalities of the lifts and working closely with each athlete. In my experience, soccer players have such limited mobility that Oly Lifts can actually do more harm (or at least waste more time) than good for athletes with a low training age or little gym experience. Regardless, I recommend keeping full Oly Lifts out of your in-season training, and using Clean pulls or snatch-grip pulls in the pre-season, if at all. There are so many other ways to train power effectively without the added complexities and potential for risk that Oly Lifts bring.

An example of medicine ball power training, dug out of our archive:

A last note on power training: repetitions should remain low and rest times regular when training speed and power, because this fitnes quality is not about exhaustion. Fatigue will remove the ability to perform at 100%, to be explosive, or to move well. A quality rep range for plyos, slams, and swings, for example, is 3-6 reps with adequate rest (1-2min) between sets. Fatigue is not the goal; a faster recovery and a higher intensity of output is. You will not get that with high volume training!

CONDITIONING

Unless you are (working with) a goalkeeper who follows in the footsteps of Manuel Neuer’s sweeper-keeper style, it’s unlikely that you need to explosively run over 10 meters, 20 at the very most.

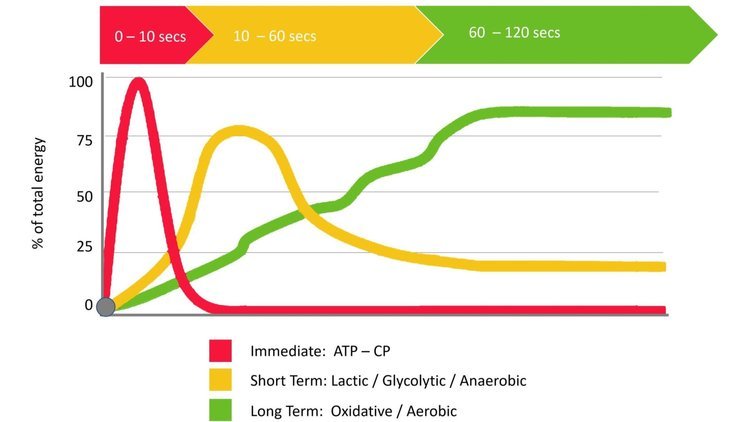

Keepers spend most of their time working anaerobically in the first two energy systems. More specifically, this means that a goalkeeper, while sprinting, diving, or flying to make a save and then resetting the tempo of the match by sending the ball back in, function in the ATP-CP system and Glycogen system, both of which are anaerobic (creating energy/ATP quickly without oxygen).

Because keepers are in action for less than 10-20 seconds at a time and then likely experience a lull in physical movement while their field players push up, they remain in these anaerobic systems. This allows them to recover relatively effectively between actions and exert 90-100% power per action, as they are short and explosive.

A brief look at the three primary energy systems. Keepers use the first two, while field players stay in the third system.

So, while field players (especially midfielders) might run 8-12km per match and spend the entire match in the aerobic energy system (minimal recovery, continuous action at 60-80% of maximal outputs, oxygen required to create energy!), a keeper must be ready to work at high intensity, react quickly, and move within a limited area. When we compare positional demands, one can fairly quickly conclude the following:

Goalkeepers have no business doing long slow runs, suicide sprints with little/no rest, or other heavy conditioning work.

A keeper-friendly protocol that has worked wonderfully as of late (both White Lion Athletes and our U19 goalkeepers at TSG Wieseck) is adding 2-3 300m shuttles to the end of training 1-2x per week. The goal here is maintaining an appropriate baseline of cardiovascular fitness and health, while not detracting from keeper-specific demands by requiring slow, fatiguing runs.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that goalkeeper training sessions are intense and absolutely exhausting. A keeper who attends team training, gym workouts and/or speed work, and goalkeeper training has likely built up a solid level of conditioning, simply by pushing through a training week. Adding any more conditioning should be considered carefully on a case-by-case basis, where a coach can help the player manage their load.

Long, slow volume, however, will bring a keeper less fitness than they bargained for, potentially raise injury risks, and reinforce exactly the opposite kind of movement they need for their position.

Keep it fast!

—————————————

Goalkeeper training and keepers themselves have become incredibly athletic in the last 20 years. That is a good thing!

Don't get left behind by training in a way that doesn't meet this position's demands for power, maximal strength, and acceleration speed. Spend time improving the fitness qualities specific to keepers; this should keep them explosive, healthy, and consistent for as long as they would like to play.

There is more to goalkeeper training, like arm care, shoulder mobility, and technical and tactical elements, but those are qualities to be discussed on a podcast with an expert… more on that to come.

As always, thanks for reading. Stay fast.